What is special about Roman and Pompeian wall paintings?

- anekah5

- Jan 10

- 9 min read

Ancient paintings give us the opportunity to immerse ourselves in the lives of people from long ago. How did they live? What did they do? How did they present themselves to others? In which rooms did they feel comfortable?

The splendour of Roman wall paintings deeply impresses us today, and we wonder how and why people back then created such magnificent paintings.

I want to explore this here and show how Roman wall paintings were created and how to recognise their special features.

Is there actually a difference between Roman and Pompeian painting? Pompeian frescoes may seem more familiar to us than Roman wall paintings, but that is solely because most of the preserved examples of wall paintings are found in Pompeii. Such wall decorations existed throughout the Roman Empire, but only in Pompeii have they been so well preserved. So they are just two terms for the same thing.

Contents

Historical context

The Roman self-image

The art of wall painting

The different styles

Themes of Roman frescoes

The garden

Greek culture

Summary

Historical context

We should not forget that it is an incredible privilege for us today to be able to view these paintings. The period we are talking about here ranges from around 300 BC to the 4th century AD, i.e. the time of the Roman Republic and then the Roman Empire. Most of the preserved frescoes come from Pompeii and surrounding towns such as Herculaneum and Oplontis, which were buried in a very short time during a spectacular eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD and thus preserved for us.

In addition, although there were also murals in simple residential houses and public buildings, the majority were found in the villas of the elite and were therefore only accessible to the inner family circle and the corresponding social classes.

Today, we can therefore get an idea of how people lived at that time and, above all, how they saw and represented themselves.

The Roman self-image

The Romans were descendants of simple shepherds and, after their conquest, also of the Etruscans. After their unexpected victory over Carthage and the Macedonians, they suddenly found themselves the undisputed rulers of the Mediterranean region and saw themselves as the rightful successors to the empire of Alexander the Great.

This explains their great admiration and appropriation of all things Greek and the fact that every citizen of a certain standing somehow behaved like a king.

The expansion of the Roman Empire not only brought great wealth to the centre of power, but also provided an insight into how the Hellenistic kings resided. And so the Romans began to rebuild these palaces for themselves, but larger and more beautiful.

The art of wall painting

Pompeii's importance for our understanding of ancient wall paintings cannot be overestimated. Almost nothing remains of the original Greek wall paintings. A rare example is the Macedonian tomb of Agios Athanasios from the 3rd century BC. In contrast, many Hellenistic images have been preserved as Roman copies in the form of frescoes and mosaics.

The brilliance of the colours that impress us so much today is based on a simple and very old technique: fresco painting. This involves applying a thin layer of lime plaster and painting on the surface while it is still wet. The carbon dioxide in the air reacts with the lime and turns into calcium carbonate. This bonds the paint to the plaster, creating a polished-like surface.

Not all pigments were suitable for this technique. Earth tones such as yellow and red ochre, Veronese green earth, white chalk or lime, Egyptian blue (an artificially produced colour made from a copper compound) and black from soot or charcoal worked best. But the most commonly used colours were reds: cinnabar red and a burnt ochre with a particularly high red content, which also became famous as Pompeian red. Punic wax was used as a binding agent, which added to the effect of a polished surface.

Most of the paintings were created by anonymous artists. There was a division of labour between the colour grinders, the figure painters, the background painters and the master, who also designed the artwork. Working in fresh plaster requires a certain speed. And you can see that in many of the paintings: you can clearly see the brushstrokes, colours are simply placed on top of each other to achieve plasticity, and there are hardly any delicate colour transitions. The process of painting is still clearly visible in the final image.

The different styles

There are four different styles, which are referred to as ‘Pompeian’ but can be found throughout the Roman Empire. They follow each other chronologically, but also mix and merge repeatedly.

The use of illusionistic painting to decorate walls was an ingenious artifice employed by the Romans to express their newly acquired status with relatively modest means.

The first Pompeian style (approx. 300-100 BC)

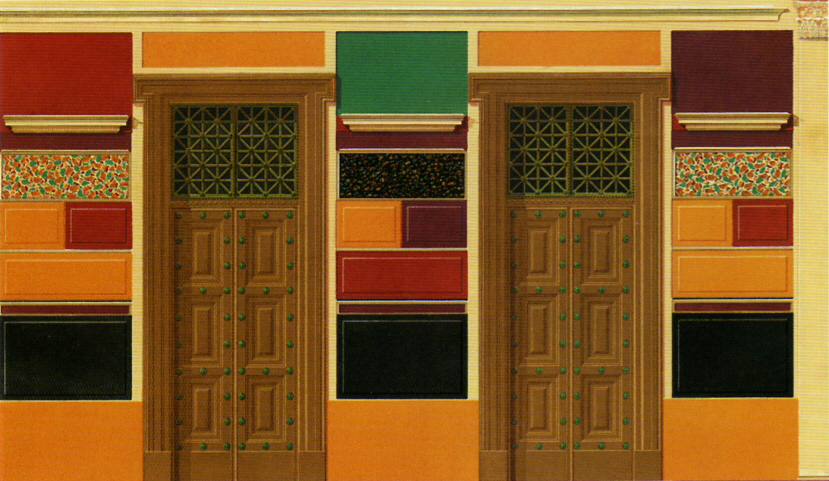

A fairly simple technique is used here: lime plaster is applied to the wall and carved to imitate expensive materials such as rare marble. The wall is divided into vertical orthostats (columns) and horizontal friezes and blocks.

1 Stabiae, Villa di Ariana - 2 Rekonstruktion Pompeji, Casa di Sallustio - 3 Herculaneum

The second Pompeian style (approx. 80-20 BC)

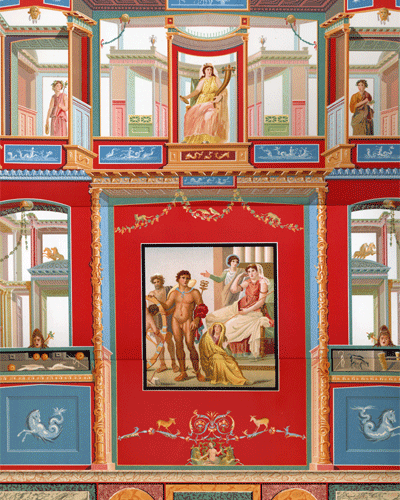

In this stylistic era, perspective was introduced and walls were completely broken up visually. One has the impression of seeing through the wall; onto further architecture or into a garden. Architectural elements such as columns, pilasters, arches and windows were painted onto the wall rather than built. The illusion of candelabras, flower garlands and statues standing in front of the wall was created. Trompe l'oeil painting thus reached its peak, creating rooms of unprecedented opulence. Paintings depicting Greek mythology were integrated into the wall design.

1 Pompeji, Villa dei Misteri - 2 Boscoreale, Villa Publius Fannius Synistor - 3 Oplintis, Villa Poppea

The third Pompeian style (c. 15 BC – 50 AD)

Under Emperor Augustus, a new modesty was propagated. The exuberant design disappeared, and walls became flatter again. They were usually divided into three parts, both horizontally and vertically. The base area was mostly dark, while the upper area was light and divided into smaller sections. In the middle zone, we see larger areas of colour framed by delicate ornaments. In the centre of the areas there is either a central image or individual, small, floating figures. In some cases, the pictorial stories occupy the entire middle part of the wall design, as in the Villa of the Mysteries. Strict symmetry is maintained. This gives everything a peaceful and orderly appearance. Idyllic and romantic themes are explored.

1 Rom, Villa Farnesina, 2 Pompeji, Haus des Jason - 3 Boscotreasce, Villa Agrippa Postumus - 4 Oplontis, Villa Poppea - 5 Pompeji, Villa Marcus Lucretius Fronto

The fourth Pompeian style (approx. 50–79 AD)

This style was first used in Emperor Nero's Domus Aurea in Rome, but its most famous example is the Villa of the Vetiier in Pompeii. Until the destruction of Pompeii in 79 AD, it continued to develop, reintegrating architectural elements, copies of paintings and illusionistic details from all previous styles. Lavish marble imitations were also used again. However, realism was no longer a priority; instead, everything was combined in a way that was sometimes very fantastical. Three-dimensional architectural details were placed amid flat ornaments; curtains hung from nothing; plants were neither purely realistic nor purely ornamental. The main thing was that it was magnificent!

1 Herculaneum, Palestra - 2,3 Herculaneum - House of the Grand Portal - 4 Rom, Domus Aurea - 5 Pompeji, House of the Vettii

After the eruption of Mount Vesuvius

Wall paintings can still be found until the end of the Roman Empire around 400 AD. However, there are of course far fewer examples of these, as they were not frozen in time as in Pompeii, but fell victim to natural decay.

But basically, it can be said that some key features were retained over the centuries: the division of the wall into vertical and horizontal zones, the demarcation by ornamental bands or columns, and the depiction of deities. Over time, fewer and fewer architectural elements were incorporated, the wall became visually flatter, and the colour palette gradually became poorer.

The themes of the Roman frescoes

The garden

As we have already seen, the Romans were originally a farming people. Every house had a vegetable garden. But with their new social self-image as lords and ladies, this picture changed. The garden became a place of pleasure and leisure. Surrounded by colonnades and decorated with fountains, mosaics and statues, the garden became a lively, hidden part of the house.

Roman nobles liked to be portrayed as shepherds and imitated the zoological gardens of Hellenistic rulers in their paintings. Where there was no direct access to the garden, surrounding murals replaced the view outside, as in the Villa di Livia in Prima Porta.

Greek culture

As heirs to Alexander the Great, they surrounded themselves with everything Greek: the language, the myths, the art. The imitation of Greek culture was particularly evident in the second style. Paintings depicting Greek gods and heroes were integrated directly into the designed wall surfaces. This resulted in entire galleries along the walls. Friezes with smaller motifs adorned the upper areas, and Greek ornaments such as meanders and Corinthian columns were used everywhere.

In the House of the Cryptoporticus in Pompeii, the story of the flight of Aeneas and his father Anchises after the fall of Troy is prominently told. They fled by ship to Latium, where Anchises founded Alba Longa: the city from which Rome later emerged. This creates a direct link between Greek and Roman history and legitimises the Romans as the successors of the Greeks.

Religion and Ritual

Roman religion was polytheistic and based on a local peasant religion in which there were personifications of nature and natural phenomena. Examples include Tellus, the earth, and Ceres, the crops. From the 5th century BC onwards, the Romans imported Greek deities and equated them with Roman ones. Dionysus became Bacchus, Zeus became Jupiter, and so on. This resulted in a great deal of overlap between the two religions, and often both Greek and Roman names were used. As soon as the Roman Empire conquered further provinces, it also incorporated their deities, who were then worshipped alongside the existing ones. This gave rise, for example, to a distinctive cult around the originally Egyptian goddess Isis, who as the Great Mother primarily stood for fertility, happiness and eternal life.

There are countless individual depictions of deities and mythological figures. Prominent examples of the representation of religious content include not only the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii, which shows the initiation of a girl into the cult of Dionysus in large panels, but also the Temple of Isis in Pompeii.

Summary:

How can Roman and Pompeian wall paintings be recognised?

That was quite a lot of information about Roman wall painting for a start. So here is a brief summary.

Time:

Wall paintings were produced throughout the entire existence of the Roman Empire, but most of the best-known examples date from the period between approximately 100 BC and 79 AD.

Location:

Roman murals can be found throughout the Roman Empire, including north of the Alps, in Turkey and in North Africa. However, the most numerous and best preserved examples come from the settlements of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabiae, Oplontis and Boscoreale, which were buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. This is why they are also referred to as Pompeian murals.

Technique:

All Roman wall paintings were executed using the fresco technique.

Colour:

Earth colours were mainly used. Various shades of red were used particularly frequently, which is why the term ‘Pompeian red’ became established for the most widely used colour.

Stylistic features:

There are four Pompeian styles, but they sometimes merge into one another and are combined.

The greatest genuinely Roman invention in wall painting is the division of the wall into three horizontal zones and usually three vertical zones as well. This creates panels that are framed by ornamental borders and tendrils and are designed differently across the surface. For example, with paintings (copies), individual depictions of gods or ornaments.

The entire room is always painted, including the ceiling. Not only white is used as the base colour, but mainly red. However, ochre, blue and even black are also commonly used.

In addition to purely ornamental designs, architectural elements are also frequently depicted. These are usually three-dimensional (in contrast to the flat ornaments).

Themes:

The most common theme is depictions from Greek culture. Ornaments, but above all mythological depictions, establish the Romans as the legitimate successors to the empire of Alexander the Great.

Religious depictions include Greek, Roman and Egyptian deities, but also depictions of rituals.

Finally, garden depictions are very popular and can be found in many villas.

So, that was my brief introduction to Roman wall painting. Did you learn anything new? I certainly hope so, because although I have been studying historical paintings for a long time, I discovered lots of new details while researching this article, which has deepened my enthusiasm for this art form even further.

If you feel the same way, feel free to share this article with your knowledge-hungry friends!

If this article has inspired you to learn more about Roman culture or even give your home a Roman touch, feel free to browse my website and shop. You'll find knowledge and inspiration everywhere.

Comments